Living Landscape - Man woven patchwork blanket for all creatures

It is rarely possible to identify one or two key factors that explain the worsening status of many species. The overarching reason to be blamed is the disintegrated landscape. Habitat fragmentation, green filed investment, urbanisation and intensified monoculture farming destroy the functional and structural diversity of the landscape.

Stop spatial development

The difficulty in formulating realistic, yet effective environmental offsetting is that, although an action plan to halt the ecological disaster is known, there is currently no real political motivation to deploy it, either at national or international level. Therefore, the most socially acceptable method must be chosen rather than the ecologically best method.

The most ecologically successful action plan would be to stop land development immediately, while maintaining the existing rules on wildlife protection. The disintegration of the landscape is the greatest threat to the wildlife of the Carpathian Basin. Spatial developments (housing developments, industrial parks, surface infrastructure, urbanisation) affect the entire life cycle of many species, from feeding strategy, breeding site selection, breeding success to migration routes. Thus, before any species conservation and habitat development plan is drawn up in detail, it must be made clear that, without a complete reduction in land development, classic practical conservation measures can only partially compensate for adverse population changes and population fragmentation caused by land take, and only for a limited period of time.

However, until political decisions are taken to safeguard the integrity of the landscape, there is no alternative but to implement measures that can be implemented on a small scale in many places, but which have a systemic effect in terms of their overall impact.

Veteran Tree Reserves

The recommended stepping-stone model for birds is called ‘Veteran Tree Reserve’ (VTR). Veteran trees are often the sites of complex interactions with other organisms — some that require characteristics only found on mature trees, such as large parts of dead wood and decay. Research has revealed that these trees are veritable arks of biodiversity, with species richness comparable to or exceeding that found in natural forests[1]. Solitary trees when they reach large size are the light towers for birds in the landscape, especially when a landscape is dominated by plain arable fields.

The Hungarian landscape, unlike some other European countries as England, lacks a large number of old trees. Historical, cultural and legislative factors played role over the past two centuries that most of the ancient tree specimens disappeared from the rural countryside. Mature, resilient tree specimens represent more than purely a component of the landscape aesthetics. These, sometime many hundred-year-old trees are biodiversity hotspots in the landscape across a number of consecutive generations. Whether or not these individualistic trees can significantly contribute to the stability of some bird populations, depends on their distribution and density in the landscape.

We recommend to establish a network of VTRs in the Őrség National Park operational area, where the national park’s service can be in charge for site management. Both newly planted young trees and designated old specimens would constitute the network of VTR. VTRs can be either solitary trees that hold a minimum of 10 m radius circle of dense natural shrub vegetation (hawthorn, sloe, dogwood, hip etc.). Or they can form a linear landscape feature where tall trees stick out of the hedges. These microhabitats could offer nesting and/or foraging habitats for four out of our 6 investigated species.

The red-backed shrike and the barred warbler nest in the dense shrubs. Newly created shrubs get inhabited by these species relatively quickly. This impact can be expected within 3-6 years after the beginning of management, as the bushes reach the required height and density within a couple of years. The hoopoe and the Eurasian Scop’s owl are both cavity nesting birds hence they can take advantage of the natural holes in the trees only long after the trees were planted. As natural tree holes appear after many decades, this is a long term investment into biodiversity and its fruits cannot be harvested within a couple of years. But, once the trees grow strong enough to hold a nest-box for scops owls/hoopoes, artificial nest box schemes can provide nest sites.

Hedges and solitary trees hold value for the biodiversity and for the landscape if their lifespan overarch centuries. This longevity was ensured in the United Kingdom since the early medieval era, as hedges and planted trees displayed field boundaries and the preservation of these landscape features became an organic part of the culture (up to the 1950’s when post-war industrial agriculture eliminated a great deal of these wildlife corridors). Pollarding[2] resulted in long life as it encouraged canopy rejuvenation, maintained the root mass, and reduced static loading on trunks and branches, even when they were decayed.

There is no explicit legal protection of hedges and hedgerows in Hungary. Individual trees also rarely enjoy any statutory protection.

Traditionally the boundaries of land were not marked with linear landscape features such as stone walls, hedgerows or earth banks. Moreover, communist collectivisation eroded many of the former landscape boundaries (dikes, treelines).

HABITAT AND SPECIES MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR BIRDS

DaRe to Connect - Supporting Danube Region’s ecological Connectivity by linking Natura 2000 areas along the Green Belt DTP2-007-2.3

Concept Note written by Ákos Klein 2019

Background

Two priority species, the Woodlark (Lullula arborea) and the Eurasian Scop’s Owl (Otus scops), and four other bird species; Hoopoe (Upupa epops), Common redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus), Red-backed shrike (Lanius collurio) and Barred warbler (Sylvia nisoria) were surveyed across the entire territory of Vas County. Various field monitoring techniques were deployed during the two-year study period in order to reveal distribution and abundance patterns.

The bird species selected under this project are all linked to human environment at some extent. As our focus species are farmland birds, the recommended conservation measures would inevitably mean significant change in national infrastructure policy, in national site development regulation and finally in the European Common Agriculture Policy.

Yet, identifying realistic small scale conservation measures, some of the special features of birds must be taken into account.

- Their habitat preference is influenced both by the nest site requirements and by the quality of the foraging habitats.

- Because birds are largely agile, their foraging habitats might spatially separate from their nest sites. Hence, the identification of habitat preferences under a swiftly changing environment is difficult.

- Young specimens disperse and explore new habitats.

- The bird species of this study migrate.

Objectives

In this brief management action plan we intend to outline habitat development measures that can be introduced in smaller regions quickly and straightforwardly. Conservation measures can realistically implemented if decision making is not hunching under the burden of heavy administration. Hence, the proposed bird site improvement actions should fit the current legislations and financially must be independent from large external grant sources to ensure sustainability of the results. Therefore, we only considered to include areas that are managed by the Őrség National Park.

The ultimate goal of this report is to outline a set of cost-effective interventions that can increase connectivity between inhabited and potential bird habitats. Sustainability and longevity of the impacts were rather important criteria.

Habitat improvement recommendations

1) Veteran Tree Reserves

The recommended stepping-stone model for birds is called ‘Veteran Tree Reserve’ (VTR). Veteran trees are often the sites of complex interactions with other organisms — some that require characteristics only found on mature trees, such as large parts of dead wood and decay. Research has revealed that these trees are veritable arks of biodiversity, with species richness comparable to or exceeding that found in natural forests[1]. Solitary trees when they reach large size are the light towers for birds in the landscape, especially when a landscape is dominated by plain arable fields.

The Hungarian landscape, unlike some other European countries as England, lacks a large number of old trees. Historical, cultural and legislative factors played role over the past two centuries that most of the ancient tree specimens disappeared from the rural countryside. Mature, resilient tree specimens represent more than purely a component of the landscape aesthetics. These, sometime many hundred-year-old trees are biodiversity hotspots in the landscape across a number of consecutive generations. Whether or not these individualistic trees can significantly contribute to the stability of some bird populations, depends on their distribution and density in the landscape.

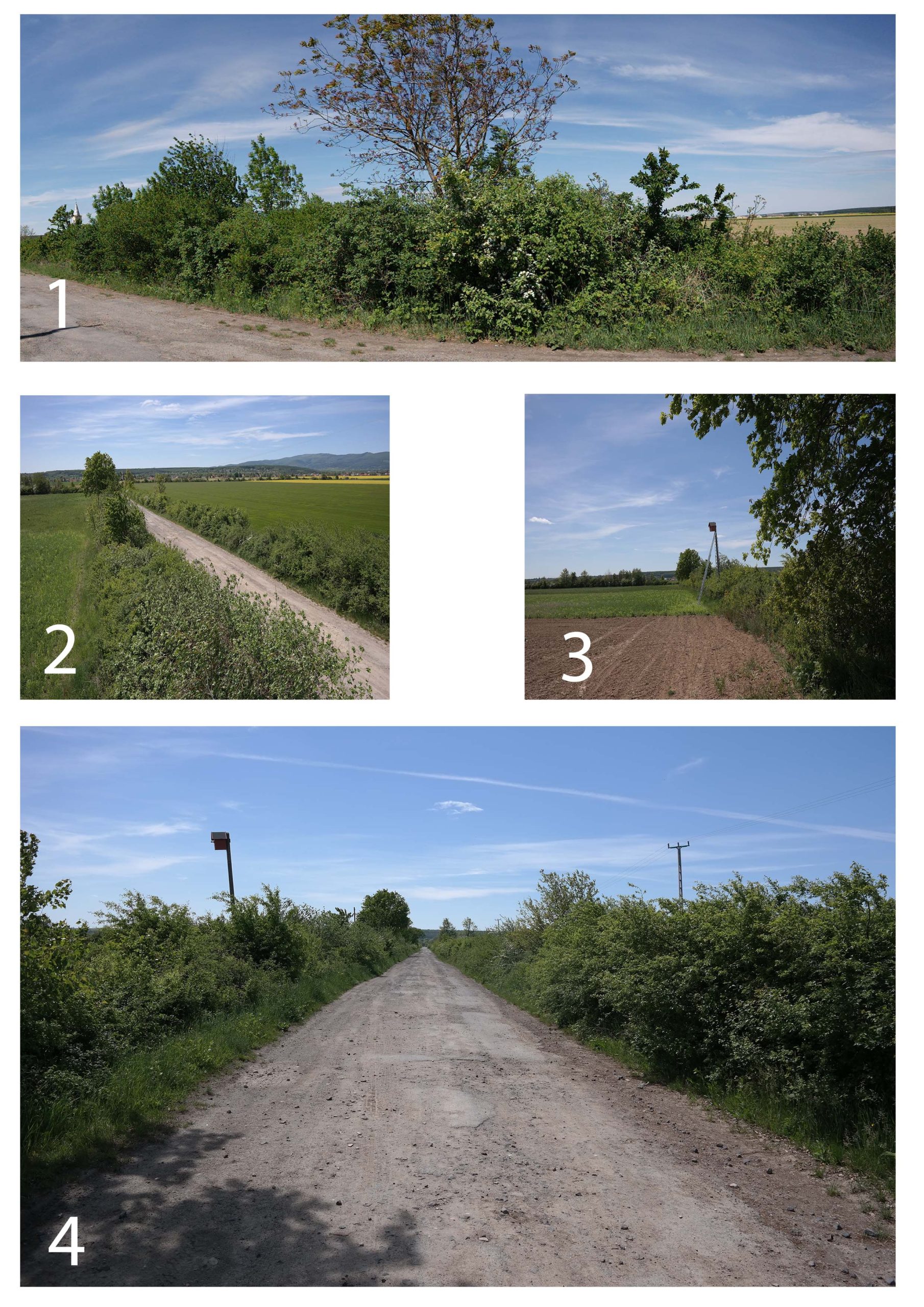

We recommend to establish a network of VTRs in the Őrség National Park operational area, where the national park’s service can be in charge for site management. Both newly planted young trees and designated old specimens would constitute the network of VTR. VTRs can be either solitary trees that hold a minimum of 10 m radius circle of dense natural shrub vegetation (hawthorn, sloe, dogwood, hip etc.). Or they can form a linear landscape feature where tall trees stick out of the hedges. These microhabitats could offer nesting and/or foraging habitats for four out of our 6 investigated species.

The red-backed shrike and the barred warbler nest in the dense shrubs. Newly created shrubs get inhabited by these species relatively quickly. This impact can be expected within 3-6 years after the beginning of management, as the bushes reach the required height and density within a couple of years. The hoopoe and the Eurasian Scop’s owl are both cavity nesting birds hence they can take advantage of the natural holes in the trees only long after the trees were planted. As natural tree holes appear after many decades, this is a long term investment into biodiversity and its fruits cannot be harvested within a couple of years. But, once the trees grow strong enough to hold a nest-box for scops owls/hoopoes, artificial nest box schemes can provide nest sites.

Hedges and solitary trees hold value for the biodiversity and for the landscape if their lifespan overarch centuries. This longevity was ensured in the United Kingdom since the early medieval era, as hedges and planted trees displayed field boundaries and the preservation of these landscape features became an organic part of the culture (up to the 1950’s when post-war industrial agriculture eliminated a great deal of these wildlife corridors). Pollarding[2] resulted in long life as it encouraged canopy rejuvenation, maintained the root mass, and reduced static loading on trunks and branches, even when they were decayed.

Figure 1. Solitary trees in dirt-road junctions (A) and linear hedges along roads (B)

Spatial considerations

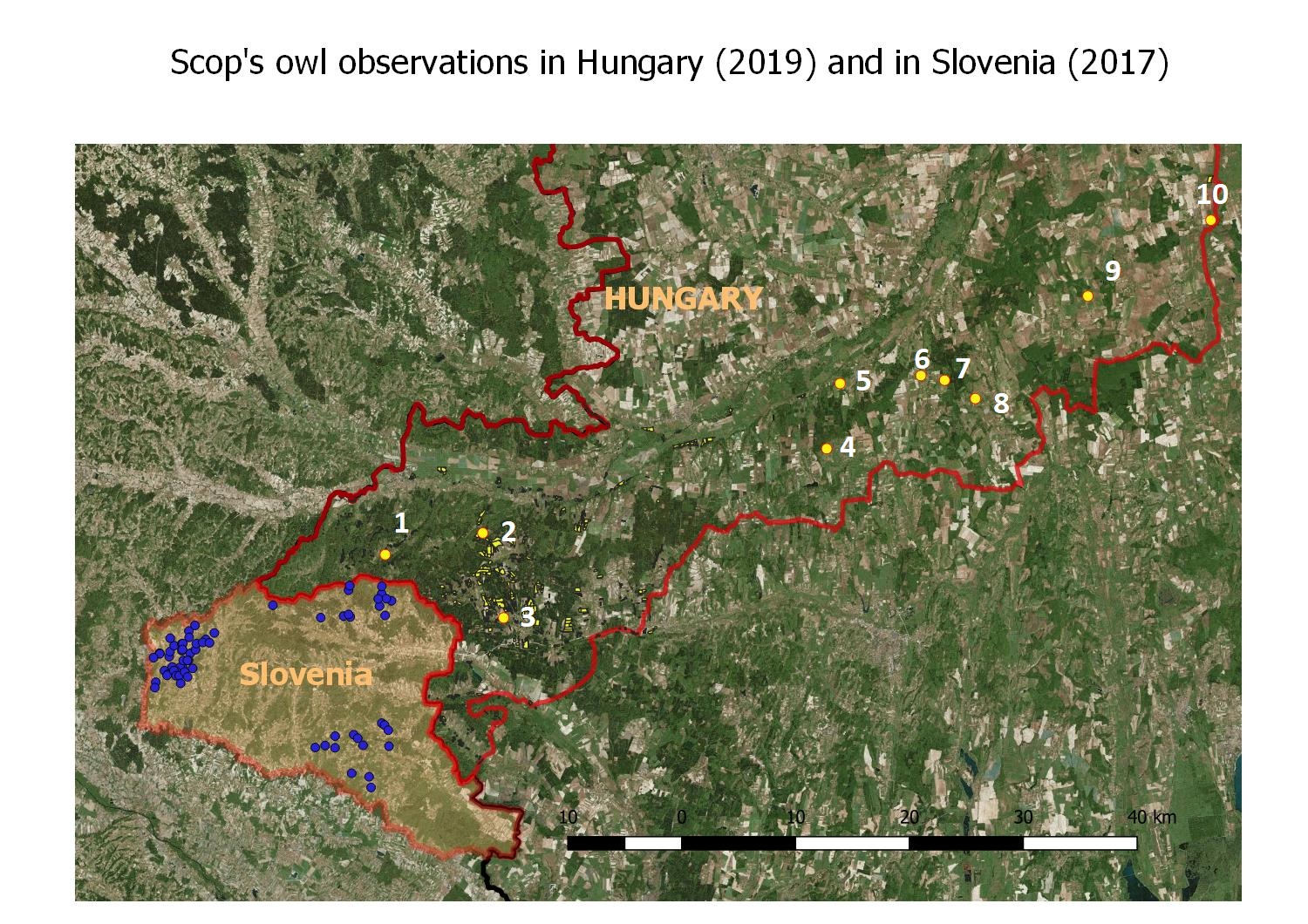

There were 10 Scop’s owl night observations recorded in 2019 in the study area. Analysing mean distance between the 10 points with the nearest neighbour method (QGIS) showed that locations are slightly spatially aggregated. The observed mean distance is 6862 m (the expected mean distance is 7962 m, Z-score: -0.8356). The same metrics differ largely in Slovenia (69 data points from 2017): observed mean distance 571 m, expected mean distance 1162 m, nearest neighbour index: 0.5, Z-score: -8.1). This shows that Scop’s owls nest in Goričko almost in a semi colonial arrangement in much higher density than they do in Hungary.

Figure 2. Points no. 1, 2 and 3 are all located in Őrség National Park. The NP possess large areas of pasture between point no.2 and no.3.

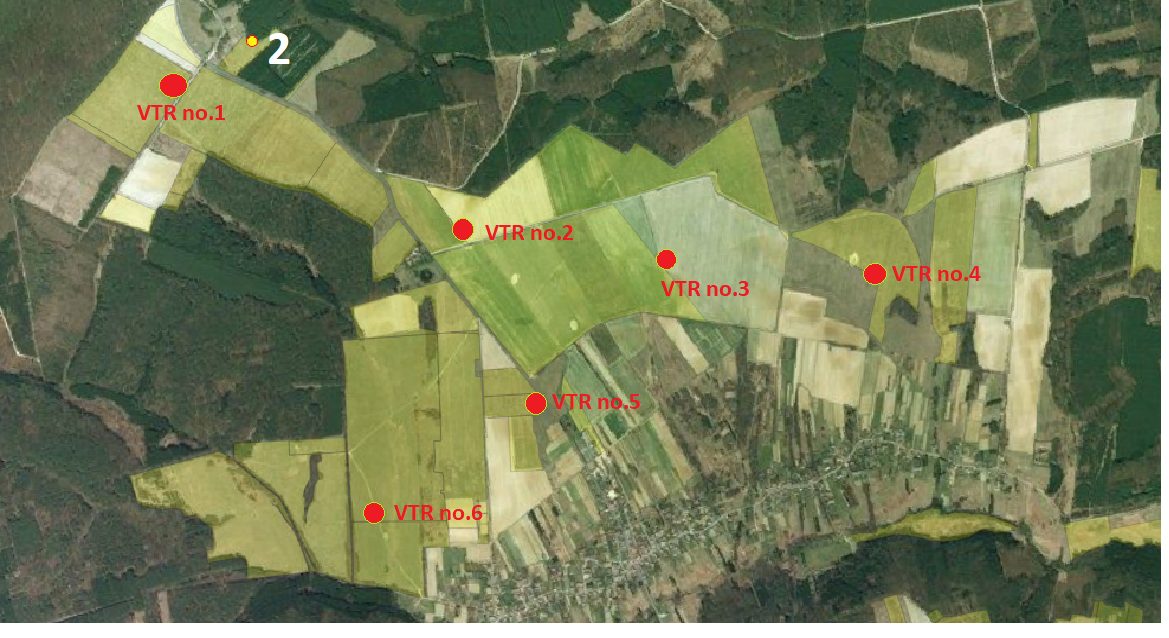

We intend to create stepping stones between the 10 observation points to increase connectivity between the occupied habitats. The VTRs are distributed in the national park’s own management areas. We excluded forests, tree plantations and land taken out of agriculture (urban areas, water bodies, quarries etc.). We selected a total of 1030 ha of managed land that comprises meadows, pasture and arable fields – in short: open habitats.

Figure 3. Open habitats (meadows, pasture, arable land) managed by the Őrség National Park between observation point no. 2 and 3.

Figure 4. Spatial distribution of VTRs close to Scop’s owl observation point no.2.

Figure 5. Enhanced connectivity with the help of VTRs between occupied Scop’s owl habitats. White lines represent the connection between the established linear or solitary VTRs.

2. Regional nest-site supplement scheme

Scop’s owls tend to occupy artificial nest-boxes. Especially under such circumstances where the foraging habitats are satisfactory but there is a shortage of natural nest sites due to the lack of mature trees. A visit in July 2019 at the Slovenian partner revealed, that Scop’s owls nest in artificial nest boxes regardless if they are installed onto an artificial pole or in a tree. However, as the host partner reported, the nest-box occupation ratio in Goričko Natural Park is not as great as it appeared initially. The majority of the breeding-pairs still use natural tree holes in Goričko and only a fraction of the nest-boxes are occupied. In Hungary, there are several local initiatives across the country that provided evidence that Scop’s owl nest-site supplementation can be a successful contribution to the stability of a local breeding population. Hence, it is assumed that further nest-box provision can help to increase the connectivity between isolated breeding pairs or colonies.

A regional nest-box scheme can be a complementary element of the network of VTR programme. As an immediate benefit, nest-boxes would provide owls with safe and attractive nest sites shortly after their installation.

As one of the important objectives of this project is linking Natura 2000 sites along the Green Belt, a nest-site scheme in Őrség National Park, situated only a few kilometres from the nearest Slovenian Scop’s Owl nests might be a hopeful attempt to build cross-border bridges between seemingly isolated populations.

Figure 6. Three Scop’s owl territories in Őrség National Park (2019, yellow points) and several observations from Goričko (2017, blue points). Nest-boxes around yellow points can increase the size of local population and help at dispersing/connecting birds.

Implementation: as a first step, we recommend to erect nest-boxes close to recent Scop’s owl observation points, rather than investing effort into unknown areas. Scop’s owls tend to form loose colonies around optimal habitats in case there is a great availability of nesting sites as well. We assume, that locations where Scop’s owls are observed from year to year, can be regarded as optimal habitats. These areas are likely to be able to carry more breeding pairs if nest site availability increases.

3. Liaising with local stakeholders

The bird species of our study are all embedded in the semi-intensively managed agro environment. Hence, the long-term conservation of these species relies on the attitude of the local people, especially the farmers and the decision makers of the municipalities. A well-designed and nurtured networking with the stake-holders who can influence the shape and future of the landscape is vital. The elements of this public engagement process can be:

- Beyond the novel creation of VTRs, the preservation of the already existing mature trees. i) awareness raising, ii) a regional cadastre of mature trees, iii) special incentive schemes for recognition of achievement can guarantee that old trees enjoy a special protection by their owners.

- Special agreements between the national park and land owners about the management of hedges and scrub areas in order to maintain the continuity of variable scrub coverages.

- Incentive scheme for farmers for nest-site provisioning.

- Citizen science actions: publications in regional tabloids in order to find more observations of the target species, especially the ones that are easily recognisable but their direct survey is too time-demanding (Hoopoe, Scop’s Owl).

4. Updating the National Ecological Corridor Network

There are locations outside the National Ecological Corridor Network (NECN) that demonstrates high quality habitats for one or more of the studied bird species. One example is a gravel road and its adjacent arable fields between Pusztacsó and Lukácsháza. The road is not part of the NECN but during the bird survey in May 2020 we experienced an extremely high density of Barred warblers and Red-backed shrikes.

Figure 8. Proposed extension of the National Ecological Corridor Network (NECN).

Figure 9. High density of Barred warblers and Red-backed shrikes. Along-road scrub vegetation must be prevented from drastic felling/strimming. Also, individualistic trees in the hedge should gain individual protection in order to ensure long life-span to those trees.

[1] https://www.savatree.com/tt-sp-11-maintaining-old-trees.html

[2] Pollard: tree which is cut at 3-4 m above ground and allowed to grow again to produce successive crops of wood.